Background

The Miyawaki Method

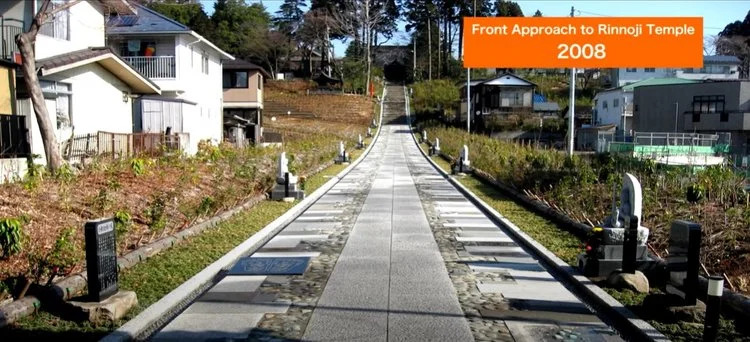

The micro forest method is inspired by the work of Japanese botanist and ecologist Akira Miyawaki (1928 – 2021), who pioneered a style of forest creation in Japan known as the Miyawaki Method.

The Miyawaki forest

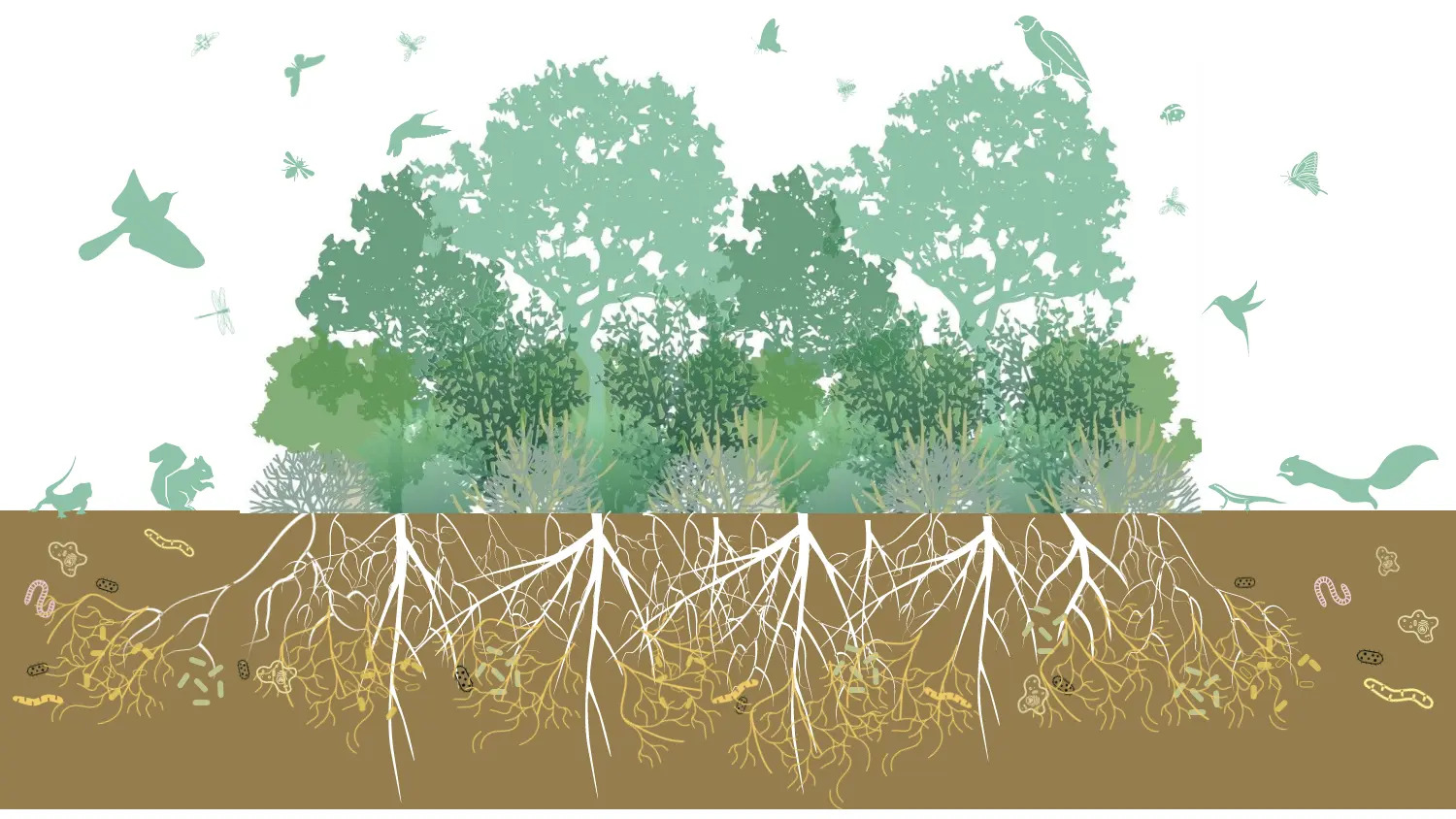

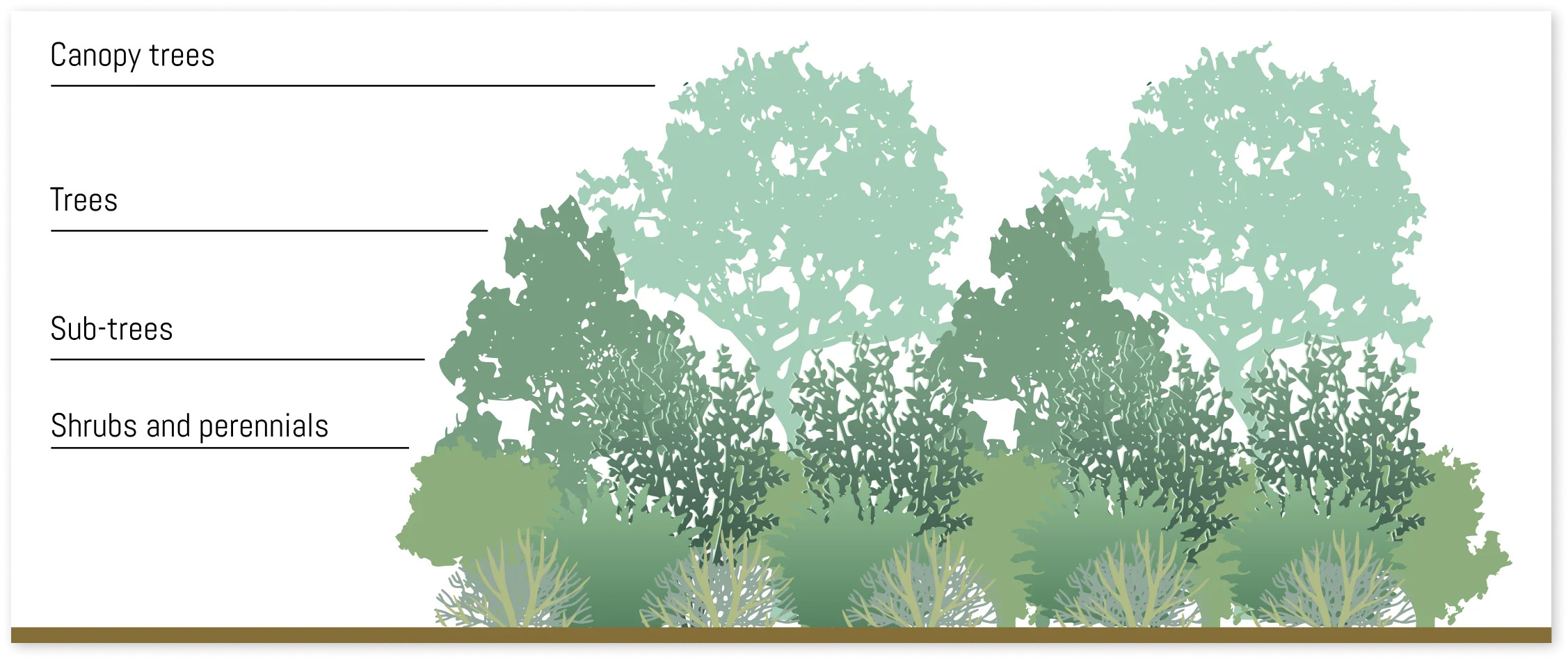

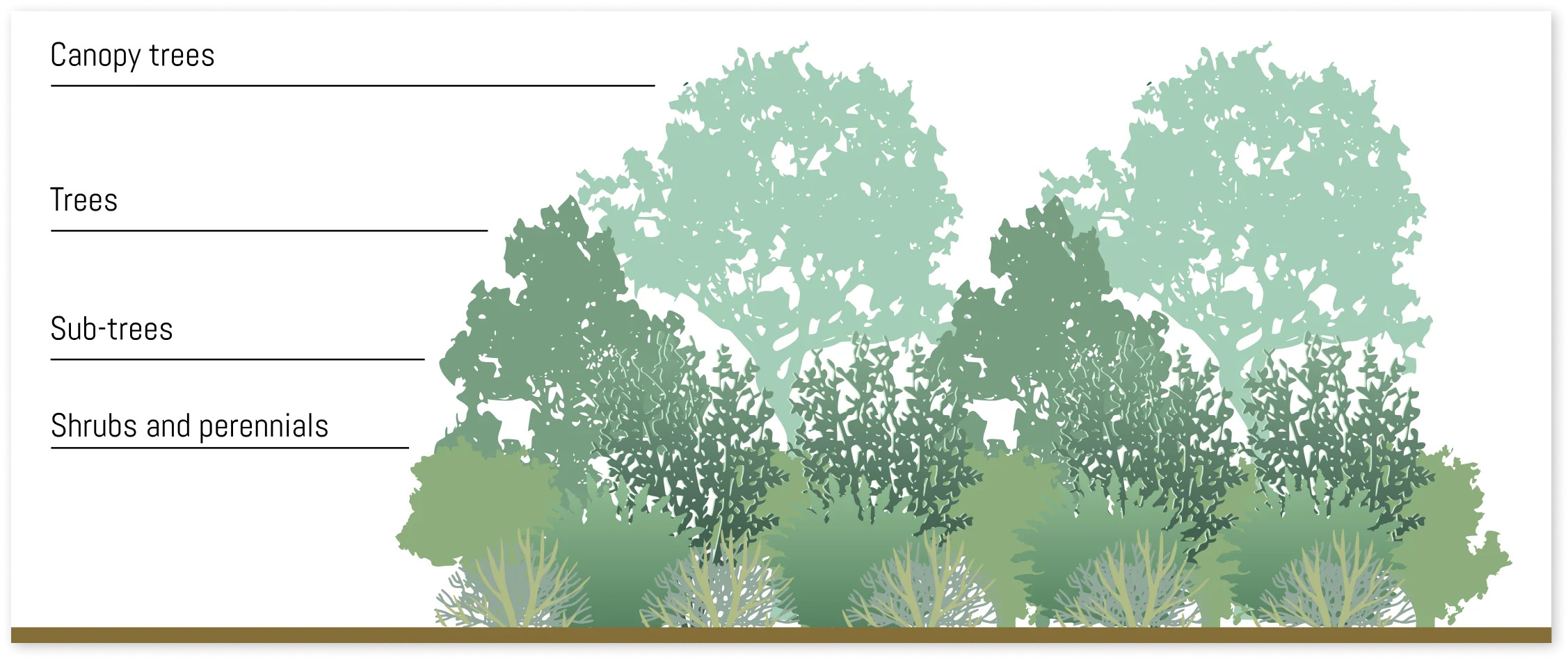

There are four layers of a conventional Miyawaki forest: canopy tree, tree, sub-tree, and shrub.

The Miyawaki method involves the randomized planting of small saplings of various indigenous shrubs and trees (grown from local, regionally adapted seeds) in very close proximity together, where no two trees or shrubs of the same height are planted side by side.

This complex layering ensures that the trees are able to grow to their ideal sizes without directly competing with a neighboring tree of the same height, while at the same time, maximizing every bit of space in the forest.

Benefits of micro forests

Grows quickly, traps carbon

This multilayered, dense planting approach creates a thick forest with a faster growth rate, improved carbon sequestration, and superior levels of biodiversity compared to conventional tree planting.

Becomes self-managing

After approximately two years of weeding and watering to set the forest up for success, the forest becomes self-managing, surviving on natural rainfall and successfully resisting weed invasion due to the dense shade and natural smothering leaf litter it produces.

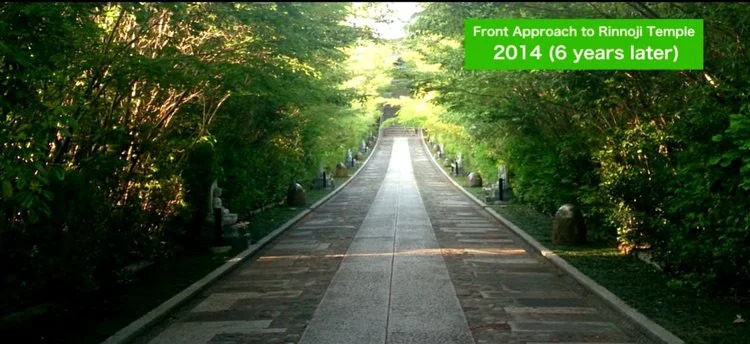

Supports the food web

The forest supports the entire food web, providing food, nesting sites, and refuge for insects, birds, and other animals that have been displaced from our urban spaces, thus facilitating wildlife connectivity and ecosystem health in our cities.

Feeds the soil

Natural leaf litter, in addition to compost and mulch, feeds the soil microorganisms, which in turn, support the health and growth of the forest.

Micro forests around the world

Because of their potential to create major impacts in minor spaces, even spaces as small as 12’ x 12’, people around the globe are using this method to restore nature in both urban and rural areas. There are excellent examples of successful micro forests in Japan, India, Europe, and the USA.

Temperate and tropical climates with higher rainfall naturally lend themselves to this method, but it is now being tested in drier and harsher Mediterranean climates as well.

Italy, Australia, and now parts of California have been experimenting with micro forests as a way to combat the current climate and biodiversity crisis.

See domestic and international examples of micro forests at SUGi Project.

The LA micro forest

Changes for LA micro forests

Changes which were made to the Miyawaki Method to make it more applicable to LA’s natural ecology are summarized below:

- The inclusion of herbaceous perennials within the lowest layer of the forest

- A higher ratio of shrubs and herbaceous perennials and lower ratio of trees compared to a traditional Miyawaki forest

- A reduction in plant density (from 3 trees/shrubs per 10 sq.ft. to 1 trees/shrubs per 9 sq.ft.)

- A reduction/elimination of tilling as a soil prep strategy

- An elimination of manure as a fertility strategy. Compost (for the addition of beneficial soil microbes more so than fertility) used instead on a case-by-case basis

- Irrigation weaned off earlier during forest establishment

Stories about LA micro forests

Check out stories about Los Angeles micro forests. We will add more real-life micro forests as we learn about them.

- Why L.A. needs micro forests (and how you can plant your own) - LA Times

- How 'micro forests' can make an environmental impact with tiny plots of land in big cities - ABC7

- How microforests can make the air cleaner and LA greener - KCRW

- Tiny Forests with Big Benefits - NY Times

- A micro-forest grows in El Sereno - The Eastsider

- Micro forest for small people making a big difference - ABC7 Eyewitness News

- Los Angeles "Eco Home" Shines Light on New Ways to Build

So... how do I plant a micro forest?

Check out our free guide